Disclaimer

- Purpose of the Article: This article brings together historical, cultural, and spiritual narratives and engages with them through a psychological lens.

- Scope and Limitations: It does not claim to offer a comprehensive or definitive interpretation.

- Nature of Reflections: The reflections presented here are part of an ongoing inquiry — shaped by lived experience, research, and critical imagination.

- Reader Guidance: Readers are invited to engage with care, curiosity, and openness, understanding that multiple truths and perspectives coexist.

Introduction: Belief Is a Choice

Belief, contrary to common assumptions, is not rooted in objective truth. Rather, it is an active psychological process—a form of meaning-making shaped by longing, trauma, and emotional necessity. Whether someone believes in a divine being, astrology, revolution, or healing, belief begins not as a rational act but as an existential choice. We tend to gravitate toward the belief that resonates with our inner fractures, then build frameworks around it: gathering evidence, interpreting signs, and constructing narratives that validate our emotional allegiance.

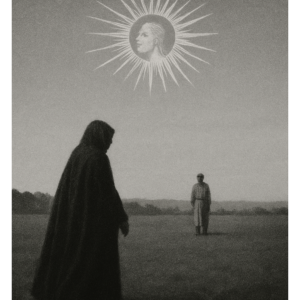

This article offers a trauma-informed psychological exploration of the life of Prophet Muhammad—one of history’s most influential religious figures. It uses concepts from attachment theory, dissociation, and visionary integration to reexamine his inner world, relationships, revelations, and the people who shaped and were shaped by him. It also considers how Islam emerged as a product of personal and collective psychic transformation and how its foundational symbols echo contemporary models of psychological healing—especially for queer BIPOC visionaries navigating their own forms of prophetic experience.

I. The Orphan and the Fragmented Self

Muhammad was born into vulnerability. His father, Abdullah, died before his birth. His mother, Amina, passed away when he was six. His grandfather, Abdul Muttalib, who briefly took him in, died two years later. By the age of eight, Muhammad had lost every primary caregiver and was finally raised by his uncle, Abu Talib—a kind but overburdened man with many children.

From the perspective of attachment theory, this sequence of early losses is deeply significant. Secure attachment requires consistent, emotionally attuned caregivers. Instead, Muhammad’s relational foundation was marked by instability and grief, which likely contributed to a disorganized attachment pattern.

As John Bowlby (1969) noted, repeated ruptures in early attachment often lead to ambivalence in adult relationships—an oscillation between emotional independence and a longing for closeness. This dynamic appears throughout Muhammad’s adult life—in his relationships, prophetic experiences, and community-building efforts.

II. Khadijah: The Corrective Emotional Experience

Khadijah bint Khuwaylid, Muhammad’s first wife, was significantly older, wealthy, and emotionally grounded. She offered not only material stability but also emotional co-regulation. Their marriage was monogamous, intimate, and deeply stabilizing. Psychologically, Khadijah served as a corrective emotional attachment figure—a source of containment Muhammad had not experienced in childhood.

When Muhammad experienced his first revelatory episode in the cave of Hira—an encounter with the angel Jibreel (Gabriel) that left him terrified and disoriented—he ran to Khadijah. Her response was trauma-attuned: she held him, affirmed his experience, and introduced him to her cousin Waraqah ibn Nawfal, a Christian mystic, who helped reframe the event as prophetic rather than pathological.

Without Khadijah’s belief and emotional grounding, Muhammad might not have interpreted the experience as divine revelation. Her presence allowed him to integrate the rupture rather than be fragmented by it.

III. Jibreel and the Idealized Internal Protector

Jibreel’s first appearance was forceful and overwhelming. He seized Muhammad and commanded, “Read!”—to which Muhammad replied, “I cannot read.” This was not a peaceful moment. It marked a psychological threshold—a confrontation with inadequacy and the demand to transform.

From a psychological lens, Jibreel can be seen as an archetypal protector or an idealized projection of Muhammad’s internal strength. For someone who grew up with abandonment and emotional inconsistency, the mind often constructs internal authority figures—voices that compel transformation and survival.

Jibreel, in this light, represents:

- The inner father Muhammad never had,

- The moral compass absent from a fragmented childhood,

- A voice of emerging personal agency.

Rather than a literal angel alone, Jibreel may symbolize Muhammad’s internalized source of power and integration.

IV. Allah as the Idealized Attachment Figure

Allah, the all-knowing, ever-present divine figure of the Qur’an, can be understood psychologically as a secure, internal attachment figure—one that offered consistency, justice, and containment in contrast to the absence of childhood caregivers.

In attachment theory, individuals who experience early loss often develop idealized fantasy caregivers to compensate for instability. For Muhammad, Allah may have served this function, becoming both a divine presence and a psychic anchor. As Muhammad’s influence grew, the voice of Allah became increasingly legislative, functioning as an internalized guide for setting boundaries, managing grief, and navigating communal conflict.

V. The Qur’an as Narrative Self-Integration

The progression of the Qur’an reflects a psychological healing journey:

- The early Meccan surahs are fragmented, poetic, and emotionally intense—mirroring trauma’s early disorganization.

- The later Medina surahs are structured, legalistic, and focused on order—indicating identity consolidation and leadership integration.

From this view, the Qur’an becomes more than a holy text—it is a map of self-integration. It charts Muhammad’s emotional evolution, grief work, and visionary synthesis of personal and communal healing.

VI. Friends, Enemies, and the Collective Attachment System

Relationships played a vital role in Muhammad’s inner and outer world. Supporters like Abu Bakr, Ali, and Bilal formed a chosen family—each representing a psychological mirror:

- Abu Bakr: unconditional support,

- Ali: familial loyalty,

- Bilal: symbolic reclamation of the oppressed self.

His adversaries—Abu Lahab, Abu Sufyan, and Quraysh elites—functioned as external representations of psychological threat: denial, dismissal, and erasure of self-worth.

Islam grew not only through belief but by offering a new attachment system—a communal space for emotional coherence and spiritual belonging.

VII. Islam as a Collective Healing Structure

Islam’s rituals and ethics can be interpreted as structured responses to individual and collective trauma:

- Prayer (Salah): rhythmic regulation of the nervous system.

- Charity (Zakat): reinforcing mutual care and interdependence.

- Fasting (Ramadan): cultivating empathy and delayed gratification.

- Ummah: establishing chosen belonging through ritual, narrative, and shared affect.

Islam, viewed psychologically, functions as an architecture of meaning—a symbolic framework developed through personal rupture, offering communal coherence.

VIII. Contemporary Parallels: Queer BIPOC Visionaries

Many queer BIPOC leaders today—artists, healers, and organizers—mirror Muhammad’s path:

- Deep wounds from early rejection or systemic harm,

- A profound vision for healing and justice,

- Public visibility alongside internal fragmentation.

These individuals often externalize their inner journey through movements and creative expression. Like Muhammad, they need grounding figures—modern-day Khadijahs—who offer affirmation, emotional safety, and containment.

Conclusion: Prophetic Integration and Modern Healing

Psychological healing today mirrors the prophetic path:

- Jibreel becomes the inner voice of strength,

- Allah becomes the internalized secure base,

- The Qur’an becomes the personal narrative of integration.

Islam, at its origin, was not a rigid rulebook—it was a living response to rupture. It evolved through one man’s journey to reclaim agency, coherence, and sacred authorship.

Today, healing does not require fear or punishment. It asks for presence, protection, and the courage to write new sacred stories rooted in trust.

Belief is not about finding one truth.

It is about creating coherence in the face of fragmentation.

And healing—like prophecy—is a form of authorship.

Extended Reflections to Follow

In the continuation of this article, deeper thematic sections will be explored, including:

- Prophetic Attachment and the Policing of Desire — examining sexuality, monogamy, and moral control.

- The Qur’an and Punishment — exploring internalized trauma, moral regulation, and symbolic justice.

These sections aim to further unpack how prophetic experiences and psychological wounds intersect with power, identity, and collective memory.

IX. Prophetic Attachment and the Policing of Desire

Examining sexuality, monogamy, and moral control

Muhammad’s intimate relationships have long been interpreted as blueprints for moral behavior. Yet, a psychological lens invites a more nuanced reading: these relationships reflect his evolving emotional needs, shaped by early loss and later responsibility.

1. Early Monogamy as Emotional Security

Muhammad’s monogamous marriage to Khadijah spanned over two decades. This union provided emotional containment and stability after a fragmented childhood. Psychologically, monogamy here was not ideological—it was necessary. Khadijah represented a secure base, offering attunement and validation he had never consistently received.

2. Later Polygyny as Political Strategy

After Khadijah’s death, Muhammad’s marriages expanded—primarily for social, political, or protective reasons. These included forming alliances, caring for widows, and stabilizing a growing community. These relationships may reflect a shift from intimacy to duty—where attachment gave way to leadership, and love was channeled into care through structure.

3. The Construction of Heteronormativity

Though Muhammad’s personal life does not overtly condemn queerness, later Islamic institutions codified his choices into moral mandates. The lived context of his relationships was transformed into doctrine that regulated bodies and desires—especially queer and female ones. Heteronormativity became a tool for maintaining lineage, inheritance, and social order—more about control than theology.

4. Capitalist and Patriarchal Legacy

As Islamic societies expanded into empires, prophetic intimacy was bureaucratized. What began as survival, grief, and care was reframed as legal structure:

-

-

Women’s sexuality became property,

-

Queer expression became criminalized,

-

Moral complexity was flattened into rigid law.

-

This mirrors Michel Foucault’s notion of biopolitical control: religion becomes a technology of power, regulating desire to serve political and economic interests.

5. Reclaiming Desire as Sacred

To reclaim the prophetic legacy today is not to mimic its form but to mirror its intent. Muhammad’s relationships reveal a path of healing, not hegemony. His ethic was shaped by need, care, and context—not moral rigidity. From this lens, reclaiming prophetic ethics means:

-

-

Seeking secure attachment,

-

Healing from grief,

-

Leading with care, not domination,

-

Loving with presence, not fear.

-

X. The Qur’an and Punishment

Exploring internalized trauma, moral regulation, and symbolic justice

Many Qur’anic verses evoke vivid imagery of hell, torment, and divine retribution. From a psychological standpoint, these passages reflect not just moral instruction but emotional intensity—suggestive of inner trauma and the need for control.

1. Trauma and the Language of Fire

The Qur’an does not merely warn against sin—it describes:

-

-

Skins melting and replaced,

-

Eternal begging for death,

-

Flames consuming over and over.

-

These verses express emotional extremes: fear, pain, rage. For trauma survivors, such language mirrors the inner landscape of the uncontained psyche—the psyche that fears re-experiencing harm and projects that fear outward as divine warning.

2. The Punishing Superego

In psychoanalysis, unhealed trauma often produces a harsh inner critic—a “punishing superego.” It says: if you fail, I will destroy you. This internal authority can become externalized in religious frameworks as a wrathful God.

From this perspective:

-

-

Hell = the internalized fear of repeating past pain,

-

Judgment = the psyche’s demand for control and accountability.

-

3. Fear as Moral Regulation

As Islam transitioned from personal transformation to political system, fear became a tool for collective behavior regulation. In unequal societies, fear replaces trust:

-

-

It ensures obedience when justice is inaccessible,

-

It resonates with those raised in violence or instability,

-

It mirrors childhood trauma—making a punishing God feel familiar, even comforting.

-

4. The Afterlife and the Need for Justice

For the oppressed, hell offers symbolic justice:

-

-

A place where oppressors face consequence,

-

A narrative of restoration when none is possible on earth.

-

Thus, hell functions on multiple levels:

-

-

As theology,

-

As emotional catharsis,

-

As political projection of unfulfilled justice.

-

5. Rethinking Punishment Today

From a trauma-informed view, Muhammad used available tools—language, myth, poetry—to structure internal and external chaos. The Qur’an reflects both spiritual truth and psychological struggle. Its power lies in its humanity: a document of fear, love, grief, and order.

6. Beyond Fear-Based Ethics

Today’s healing does not require fear:

-

-

Therapy invites integration, not punishment,

-

Accountability arises from wholeness, not shame.

-

To evolve spiritually is not to escape hell, but to stop replicating it—internally and collectively. Finding one’s own God means building a moral compass rooted in compassion, not control.

XI. The Idea of One God and the Power of Myth

Monotheism—the belief in a singular, all-encompassing divine force—has appeared across time and cultures as both a theological assertion and a deep psychological need. While its expression varies, the underlying mythos of a unified source often serves as a map for coherence in a fragmented world.

Across Traditions:

-

-

In Judaism, the Shema (“Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is One”) establishes oneness not just as metaphysical truth but as communal identity. This unity offered resistance to surrounding polytheistic empires and grounded a persecuted people in belonging and covenant.

-

In Christianity, the concept of one God exists within the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Here, divine oneness is experienced relationally: as love, sacrifice, and incarnation. The myth of the crucified and resurrected Christ speaks to redemption through suffering, a powerful motif in collective healing.

-

In Islam, Tawhid (divine unity) is the core of faith. Allah is the indivisible, eternal source of all things—beyond form, gender, or plurality. The mythic power of the Qur’an, revealed through Muhammad, positions divine speech as both guidance and disruption: a voice that reorders inner chaos and reshapes social reality.

-

In Zoroastrianism, one of the earliest monotheistic faiths, Ahura Mazda represents truth, light, and justice—locked in eternal struggle with the forces of deceit and destruction. This duality symbolizes the human experience of moral choice, anchored in a singular source of wisdom.

-

The Power of Myth

As Joseph Campbell and others have explored, myth is not a lie—it is a symbolic truth. Myths give form to the intangible: fear, desire, loss, hope. The myth of One God is not just a theological claim; it is a psychic container. It tells us:

-

-

That chaos can be met with order,

-

That pain can be held in presence,

-

That justice—even delayed—has a place in the cosmic story.

-

In this way, myth is not escapism, but structure. It builds internal worlds where external ones fail. It gives narrative shape to trauma, grief, and longing—especially for those navigating systemic violence, displacement, or inner fragmentation.

Psychological Reflection

For the traumatized psyche, especially one formed through early rupture, the idea of a singular, stable, ever-present God provides what no human ever could: consistency, attention, containment, and unconditional witness. It becomes an internalized secure base—not just a belief, but a felt sense of being held.

Thus, monotheism functions on multiple levels:

-

-

Spiritually, as submission to a higher order,

-

Collectively, as a unifying narrative,

-

Psychologically, as a process of integration.

-

Across traditions, the One God myth is not only about heaven or salvation—it’s about surviving rupture, finding meaning in suffering, and re-authoring one’s place in the universe.

Key Terms and Suggested Readings

Key Psychological Concepts

-

Attachment Theory: Developed by John Bowlby, this theory explores how early caregiving relationships shape emotional development, trust, and relational patterns in adulthood.

-

Dissociation: A psychological defense mechanism where parts of experience—such as memory, emotion, or identity—become disconnected, often as a response to overwhelming trauma.

-

Corrective Emotional Experience: A concept in therapy describing moments where a new, healing relationship or dynamic helps repair damage from earlier emotional wounds.

-

Superego: In Freudian psychoanalysis, the superego is the internalized voice of authority, morality, and punishment—often experienced as shame, guilt, or harsh self-judgment.

-

Integration: The process of bringing fragmented or exiled parts of the self into coherence and alignment—key in trauma recovery and personal healing.

Recommended Reading & References

-

Bowlby, John (1969). Attachment and Loss. A foundational work on the psychology of attachment and its lifelong impact.

-

van der Kolk, Bessel (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. A widely acclaimed book connecting trauma to the body and nervous system.

-

Herman, Judith Lewis (1992). Trauma and Recovery. A classic that contextualizes trauma as both personal and political.

-

hooks, bell (2000). All About Love: New Visions. A radical redefinition of love as a practice of liberation and healing.

-

Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider. A collection of essays and speeches on Black feminist thought, rage, love, and resistance.

-

Foucault, Michel (1978). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1. A philosophical examination of how power and discourse shape sexuality and morality.

-

Fanon, Frantz (1952). Black Skin, White Masks. A psychological and political critique of colonialism and racial identity.

-

Ahmed, Sara (2010). The Promise of Happiness. Explores how societal expectations of happiness shape lives, identities, and resistance.

-

Anzaldúa, Gloria (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. A groundbreaking text on hybridity, identity, queerness, and cultural border-crossing.